On February 28th 2017, the Indian government announced that students who wish to have midday meals in their government schools – a nationwide scheme targeted at increasing enrolment in schools – have to furnish their Aadhaar number or proof or undergo Aadhaar authentication. Cognizant of the fact that millions of children may not be enrolled in Aadhaar, the government came up with a deadline of June 30th 2017 for parents/guardians to ensure their wards have Aadhaar numbers. In the meantime, the government permitted these parents/guardians to furnish proof of their relationship to the child and declare that the child is not accepting midday meals at more than one school.

Why were the two schemes linked? The government notification in question states that the use of Aadhaar for delivery of services and/or benefits “simplifies the Government delivery processes, brings in transparency and efficiency, and enables beneficiaries to get their entitlements directly to them in a convenient and seamless manner and Aadhaar obviates the need for producing multiple documents to prove one’s identity”.

Over 10 crore students access midday meals across the country, but reports such as this cite that alarmingly low numbers of students are enrolled in Aadhaar. Given this, the government continues to go ahead with enforcing this linkage, even extending the deadline for enrolment into Aadhaar till August 31st. But after August 31st, students without Aadhaar are effectively out of the midday meal programme.

This, despite repeated reminders from the Supreme Court that Aadhaar cannot be made mandatory for welfare schemes.

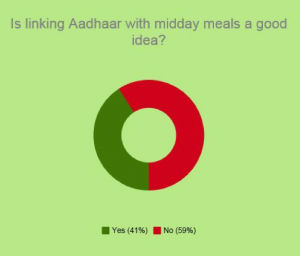

What does this linkage between the Aadhaar and the midday meal scheme bode for these millions of students in India? A Mobile Vaani Janta ki Report shares some listeners’ perspectives[1] on this issue.

Note: This is based on a qualitative analysis of the responses received.

Aadhaar and reducing corruption: tenuous linkages

Respondents who were for the move believed that such linkages will stem corruption and ensure that only deserving people benefit from the scheme. Although many of these respondents recognised that this will be another form of identification, in addition to the PAN card, license, voter ID, etc., they believed that Aadhaar will be effective identification that will ensure that beneficiaries, especially children, can take advantage of the many schemes offered by the government through their lifetime.

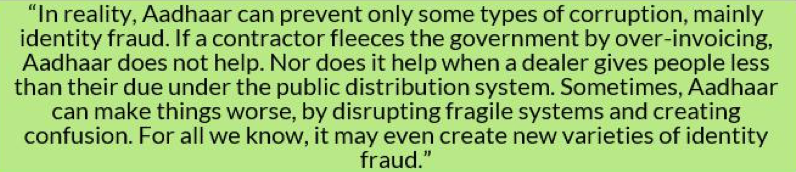

It is interesting that there is a strong belief in the role of Aadhaar in reducing corruption in welfare schemes, even as there are many opinions and facts to the contrary. Jean Dreze discusses this as one of the biggest myths that propounds around Aadhaar:

Activists are vocally against the move of linking Aadhaar with midday meals, and Jean Dreze argues that any corruption in midday meal schemes – and this is not very large – will not be stemmed with Aadhaar. Additionally, given the high failure rate when Aadhaar was linked with the pensions, public distribution systems (of food grains) and MGNREGA, this move is reported as not bringing anything positive to the table – such linkages, if anything, have been “disastrous”.

Indeed, several listeners felt too that linking Aadhaar with welfare schemes will do little to stem corruption. Commenting on the likelihood of corruption in the Aadhaar enrolment process itself, one person talked about errors in spelling or other details that sometimes occur, which meant that they had to spend time and resources to go through the process again.

Not suitable for young people

Several people argued that the government should not force Aadhaar on children or people below the age of 18. One person highlighted the practical difficulties of getting children’s biometric data at a young age (although biometrics are not required for children less than 5 years of age), while another rued the government’s tendency to take such important decisions without consulting with people. Perhaps it is acceptable for adults to mandatorily have Aadhaar to access benefits, but imposing this on children is wrong, said some listeners.

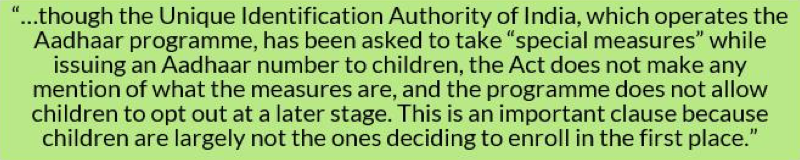

Many have discussed the issues around enrolling children for Aadhaar, especially given their consent in terms of submitting their biometrics or agreeing for lifelong tracking of their usage of the Aadhaar number is not taken/recognised. Talking about the lack of options for children to opt out of Aadhaar when they become adults, Kritika Bhardwaj from the Centre for Communication Governance at National Law University Delhi says:

Practical difficulties and Supreme Court orders

Interestingly, several listeners mentioned the Supreme Court order that rules against mandating Aadhaar for welfare schemes, irrespective of whether they were for or against the move of linking Aadhaar with the midday meals scheme.

Practical difficulties that come in the way of such mandatory linkages of Aadhaar with schemes were discussed. Some listeners mentioned the long queues for enrolment that typically formed, while others discussed that these enrolment centres were not easily accessible, both of which meant a day’s loss of pay for people in rural areas who are most likely to be daily wage labourers. One listener suggested that camps are held at schools to ensure all students enrol, something that the Ministry of Human Resources and Development has encouraged states to do.

What does the future hold?

With just weeks left before the August 31st deadline for student enrolment, it remains to be seen whether many students will be denied midday meals because they do not have an Aadhaar number. It would be a pity if the midday meal scheme, one of India’s most successful measures in improving enrolment in schools, leaves out millions of needy children for want of a to-be-voluntary unique identification number.

Mobile Vaani’s strives to be a platform that allows people to discuss what matters most to them and bring in perspectives that are often missed out in mainstream media. Through programmes such as Janta ki Report (People’s Report), Mobile Vaani aims to bring context and completeness in its discussions – context, by building on hyper-local topics of concern and delivering information using local references, languages and culture, by voices from the community; completeness, by ensuring that perspectives of a variety of stakeholders are sought in critical discussion areas, enabling listeners to get a rounded picture of the topic of discussion.