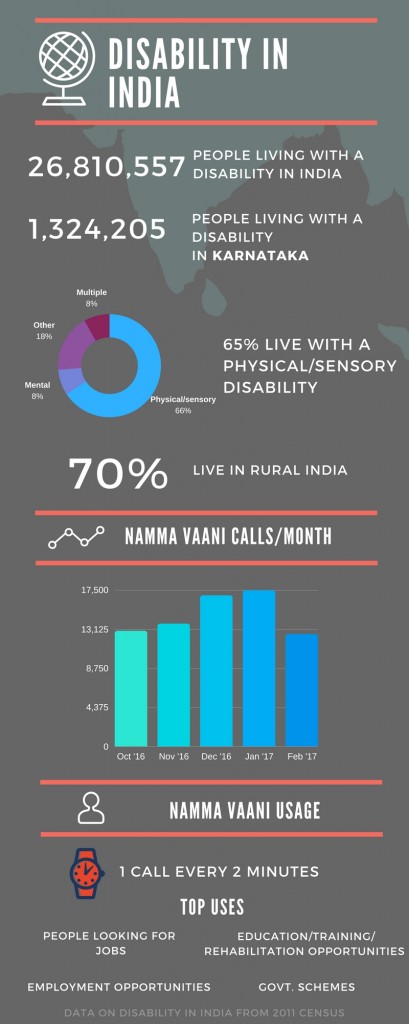

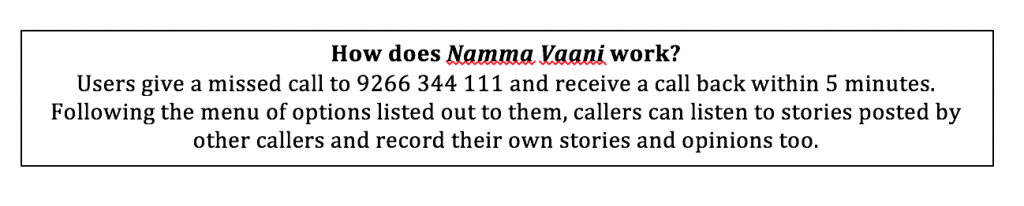

Thousands of NGOs and development organisations across India interact with the grassroots everyday – with people, their influencers, their local leaders and government bodies – as part of their programmes. Only with the right communication, can awareness gaps of people be bridged, consensus built, information exchange established across different stakeholders, and people motivated for change. Helping development organisations in their communications requirements has been one of Mobile Vaani’s critical offerings: we have worked with over 100 organizations so far including CREA on spreading the word in local communities in Jharkhand about reservation for women in Panchayati Raj Institution elections; Enable India to reach thousands of people with disabilities in rural Karnataka; PACS and their cadre of community level workers (mitras) to spread awareness about the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana; and many more. Communication platforms such as Mobile Vaani can enhance development interventions by reinforcing messages and helping the right stakeholders interact with each other.

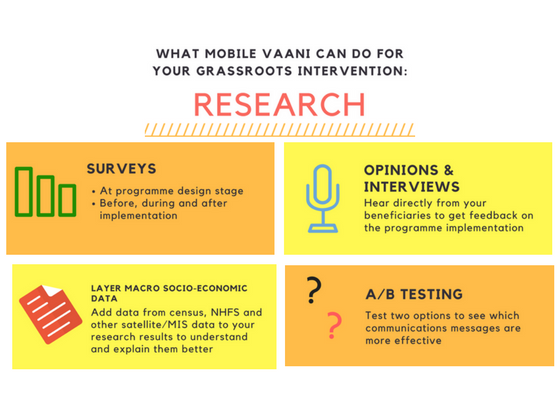

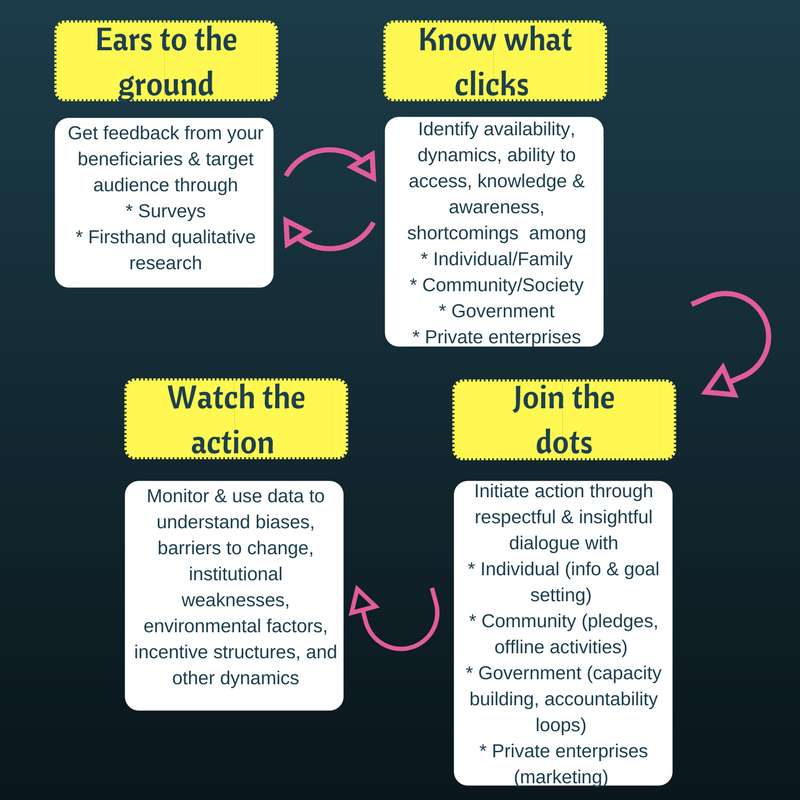

However, communication alone is not sufficient and there is a significant need for consistent and continuous monitoring of programme implementation, to ensure the programme can be modified as required to be more effective. Designing monitoring systems – that allow for monitoring and modification of the programme while it is ongoing – has to be an integral part of its design. Such feedback loops in programmes designed by development organisations often tend to be delayed and anecdotal however, based on feedback from occasional field visits and internal reviews. Can technology platforms be used to get quick feedback, and modify the strategy if needed?

Here’s where Mobile Vaani can help too: going beyond just engagement with target audience groups and related stakeholders, to leverage the communication to incorporate effective monitoring both during and after the implementation.

What can the Mobile Vaani platform do for you?

Using the platform in over 20 districts in rural central India for four+ years now with more than 10,000 users calling daily into the platform, we have gained rich experience in engaging with various levels of grassroots communities to enable the information collection capabilities at scale in grassroots development interventions. Here are a few examples of how the we are enhancing the Mobile Vaani platform to strengthen interventions, expand their reach and measure their results effectively.

How the platform helped in programme design

An example would be our work with a telecom major who approached us to check if there was scope for an electronic marketplace for selling farm output. To identify this, we ran a two-week survey, whose results told us that the bigger need for farmers was an electronic marketplace to rent tractors or trade agricultural tools (2 out of 3 farmers in our catchment area rented equipment, according to our survey). The recent establishment of FarMart, a startup that has just received funding, proves that our survey identified a critical gap.

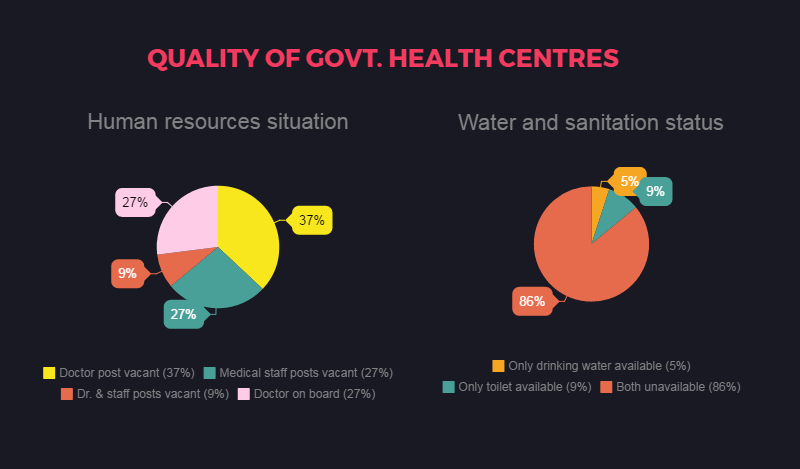

In another research project, we helped identify the right stakeholders to engage on a social issue. We worked with a large development organisation who wanted to raise awareness of government benefits under the Janani Suraksha Yojana among expecting women. A quick survey on the Mobile Vaani platform indicated that the problem was not lack of awareness (67 percent of respondents were aware of government’s antenatal care benefits) but people’s trust in the quality of the government centres where they could avail these benefits. These results helped frame the design of the project not so much in terms of awareness, but rather as a social accountability intervention which collected data on the quality of care and infrastructure in health facilities, which was then forwarded to the local government and administrative authorities for action. The reports were also featured in major regional media dailies, and led to the improvement of several facilities that impacted thousands of people.

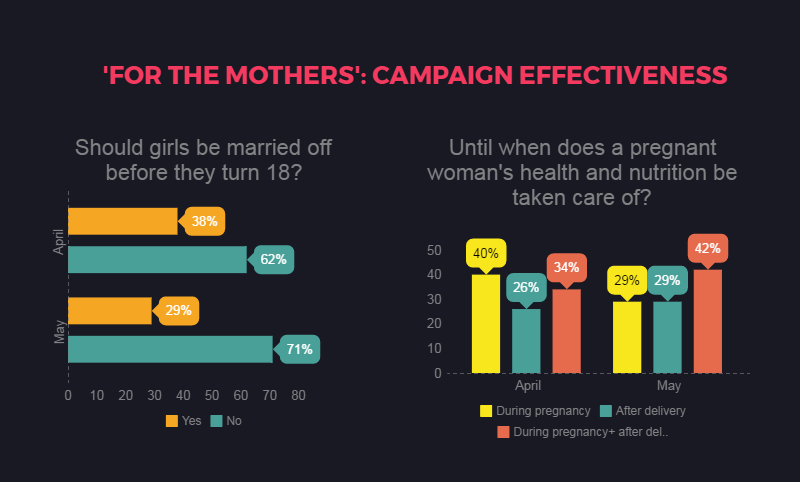

Using the platform to concurrently track effectiveness

The Mobile Vaani platform also enabled Knowledge-Attitude-Perception tracking for a campaign on maternal health. Our surveys at the beginning and end of an Oxfam programme ‘For the Mothers’ in 2015 helped us identify how users’ perceptions around various aspects related to maternal health changed through the campaign. This was followed up with a recall survey to see whether campaign messages were retained in people’s minds.

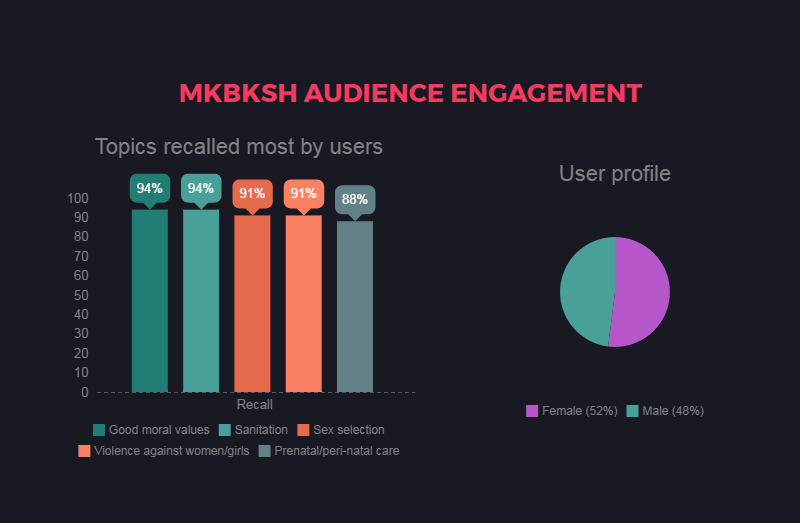

Through our platform, we can reach ‘media dark’ areas and try to bridge the gap left by communication that relies on mass media. For instance, Mobile Vaani’s IVR system was used to engage in real time the audience of the TV series Main Kuchh Bhi Kar Sakti Hoon (MKBKSH), an entertainment-education programme to promote gender equality and address social issues run by the Population Foundation of India. The IVR was used to reach audience members from media dark areas with information from the series and enabled them to provide feedback, listen to curated content and record opinions on several social issues. Over 1.7 million calls were received from 29 Indian states, proving the series’s audience engagement and positive actions taken by viewers thanks to the series, which helped PFI use the IVR system as a barometer to understand mindset changes the TV serial had brought about.

Comparing the effectiveness of different strategies

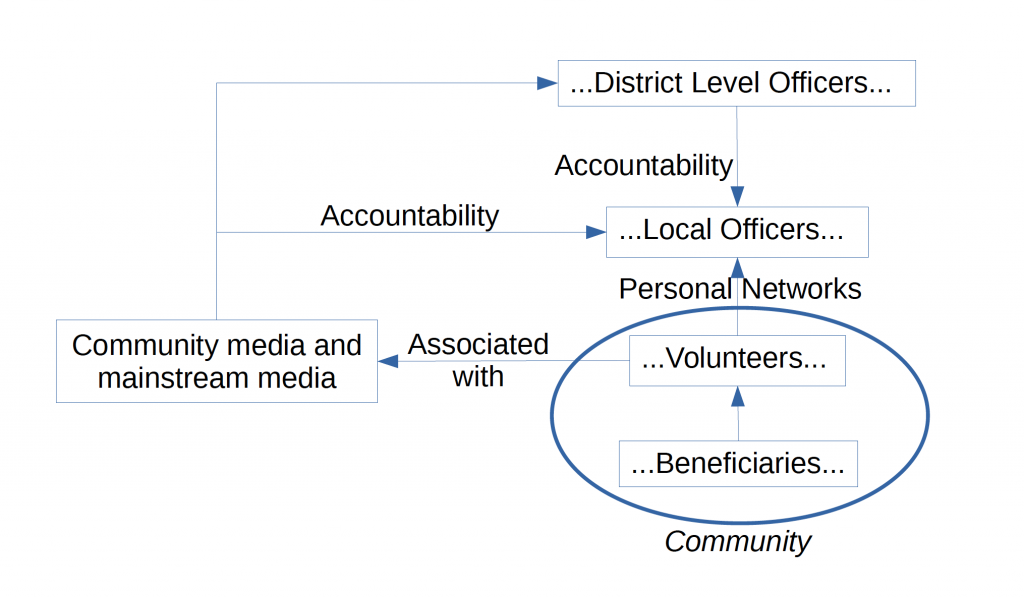

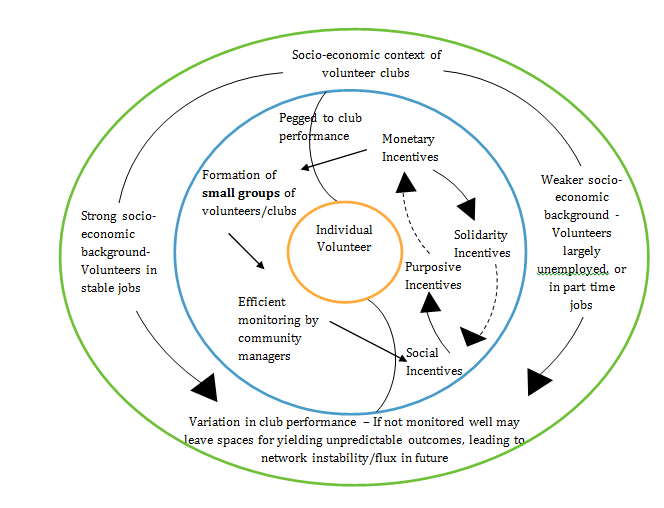

Our platform also has the capability of A/B testing: comparing two routes (of communication, action, etc.) to see which performs better. We used this in our own analysis of financial incentive structures for Mobile Vaani volunteers, wherein we tested two sets of volunteer payment methods in different ‘clubs’ of Mobile Vaani. In some clubs, we implemented a group incentive structure where the volunteers were paid equally but based on the performance of the group, and in the other clubs we implemented an individual based incentive structure based on the performance of each volunteer. We found that individual payments however led to disputes and poor performance of the clubs overall ; group payments, on the other hand, were distributed evenly among volunteers, and peer pressure and collective accountability ensured that there were no freeloaders. Clubs following the group based structures had call volumes almost four times that of other clubs on average, and grew much more quickly at a lower cost per user acquisition. Coupled with other observations to strengthen our selection process of volunteers, we came up with the following structure which shows how monetary, purposive, solidarity, and social incentives come together nicely in group structures to lead to extremely dynamic clubs.

Upcoming capabilities

Mobile Vaani’s capabilities will be further enhanced with our recent innovations, notably the introduction of our hybrid app + IVR strategy,

which will allow staff from development organisations to run demography and baseline/endline data collection surveys through the app, and run regression analysis to explain the observed effects based on the demography and user participation on the platform.

We are also overlaying census data, satellite data, National Family Health Survey data and government Management Information Systems (MIS) into our platform to help understand how macro socio-economic parameters influence the programme’s implementation and outcomes. For instance, when working in three panchayats for one of our recent programmes, we observed that traction in one panchayat was double the other two; when correlated with census data, we saw that this was the poorest community among the three surveyed – it had the most number of houses with thatched roofs, the least accessibility to drinking water and electricity within its premises.