Dear Friends of Gram Vaani,

Hope you have been well.

I had started working on a book during the pandemic, largely based on Gram Vaani’s experiences with the use of technology to secure rights and entitlements for the poor, and for them to discuss and deliberate policies and social issues with one another. I am excited to share the news that the book is now published.

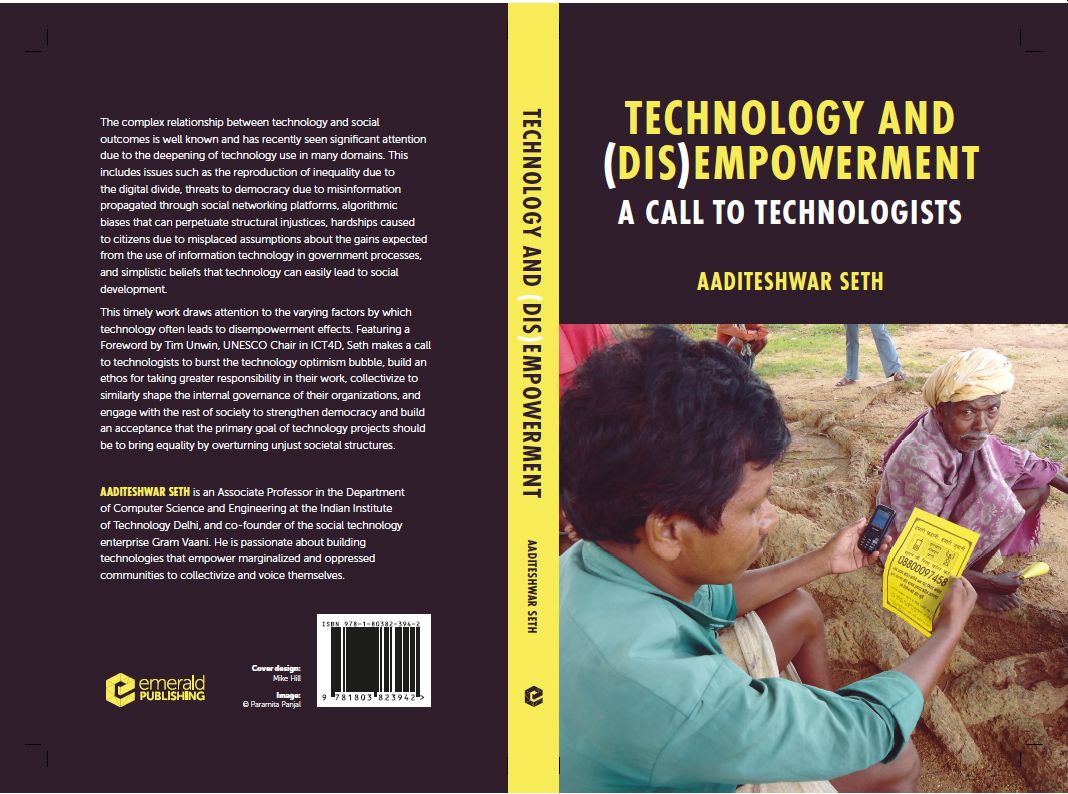

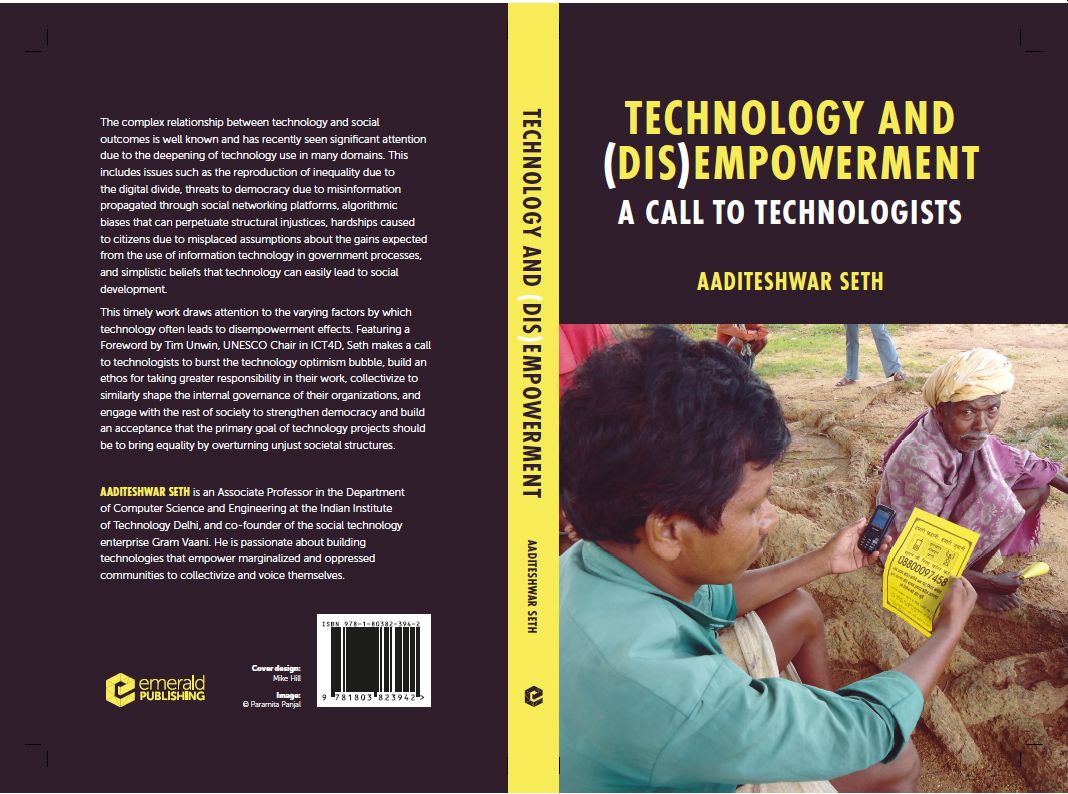

It’s called Technology and (Dis)Empowerment: A Call to Technologists. My primary argument is that the goal of technology should be to overturn unjust societal structures to empower the weak and oppressed, and that technologists should take steps to ensure that their labour gets channeled singularly towards this goal.

The book is available on Amazon.in, Amazon.com, Emerald, eBooks.com, with previews at Google Books, and you can also write to me for my local electronic version. The preface, introduction, and foreword (by Professor Tim Unwin) are available here. Some comments by eminent researchers and practitioners are mentioned towards the end of this email.

Needless to say, none of this would have been possible all the support from our partners. Gram Vaani has been incredibly lucky to have had an opportunity to work with amazing people and organizations in the social development space, to which many of us at Gram Vaani and especially me came as an outsider more than ten years back. We were warmly welcomed by the community and who worked alongside us to innovate and learn and unlearn, and the book has really emerged as an outcome from all this rich interaction.

Much of Gram Vaani’s work so far has been in the space of participatory media, for communities to share and learn from one another, use the power of media to improve local governance and social accountability, and empower marginalized groups. Based on this experience, I will try to summarize a few of the key points I have tried to make in the book – and we are eager to continue our collaborations with all our partners to apply these principles to new areas for the use of technology, in particular for gender equality, climate resilience, and public health.

First, I try to distinguish between the ends and means that a technology project may aim to meet. Most ICTs for development projects are unique in having identified some clear end goals for the projects, and which I found in Gram Vaani’s case helped provide us with a compass – a guiding light – to aim towards and to continuously steer our decision making to meet these goals. However, many technology projects adopt generic ethics statements that focus only on the means – do no harm guardrails that the projects should follow – and this I argue is not sufficient, like a ship without a compass to point it in the right direction. It could take the ship to many different destinations, not all of which may be desirable. A social good project must clearly define its end goals.

Second, what should these end goals be for a social good project? I argue that technology should be meant to bring power-based equality in the world, by removing unjust hegemonic structures that perpetuate structural injustice. If this is not the goal, then technology often tends to reproduce inequalities – being wielded more easily by those who can gain access to it, or design it for their own agendas. I draw on works by researchers like Tim Unwin who argue for the same reason that technology should be designed only for the poor, feminist scholars like Iris Marion Young who define the purpose of justice itself as showing the path to remove the underlying processes that cause structural injustice, Amartya Sen who makes similar arguments in terms of freedoms, and Marxists like Harry Braverman or technology historians like David Noble who document the processes through which technology often serves the agendas of the powerful.

Third, I delve deeper into the need to go beyond ensuring safety and equity, or goals like power-based equality, in the technology design alone. I argue that attention should be paid to ensuring the same ethical principles in the management of the technology too. I define management as what comes post-design when technology is deployed, and I argue that it is important to make this distinction between design and management because often in practice the teams of technologists playing these roles are distinct and the methods employed by them are also distinct. Most complexities at the management stage arise at the socio-technical interface when technologies begin to be used by people, and invariably lead to surprises and unforeseen situations largely due to the complexity of the world that cannot be possibly modeled completely at the design stage itself. Feedback processes to learn about these gaps, humility to acknowledge them, and proactiveness to correct them by evolving better policies or re-designing the technology systems, become essential.

Fourth, I borrow from the concepts of appropriate technology by E.F. Schumacher and the Scandinavian methods of participatory design to emphasize that the users of a technology system should be involved in its design and management. Only once the users understand the technology and are able to un-blackbox it, can they steer the technology from avoiding harms and to neatly handle exceptions in their diverse local contexts. This has always been a key principle for us at Gram Vaani, and led us to develop the hybrid online-offline Mobile Vaani model – where the online technology is governed by an offline team of community volunteers. It is the volunteers who are able to ensure a close embedding of Mobile Vaani within the communities, convey editorial preferences for the content carried on their platform, and ensure that all operations adhere to the ethical principles of inclusion and empowerment of the weak and oppressed. We have always endeavoured to get to a point where the technology simply becomes an infrastructure, and community institutions such as the Mobile Vaani volunteer clubs do the rest.

Fifth, I discuss what might prevent technologists from following these principles above. I delve in detail into the current structures of the market and state that often compromise these values, either by design or by sidelining these principles in favour of other objectives. Profit-seeking goals of corporations, or social control goals of the state, and often interlocks between the two, infiltrate multiple spheres that lead to fallouts from technology. They infiltrate organizational culture by creating role-based segregation and moral buffers for various teams. They influence the incentive structures for technologists by emphasizing profit-maximizing metrics rather than impact-maximizing or harm-avoiding metrics. And in the current context of increasing digitization led by centralized architectures they inevitably lead to surveillance based models which at worst are designed to disempower individual and group freedom, or at best are highly error prone and often not scaffolded by fault-managing systems like for grievance redressal.

This is why the book is really a call to technologists to realize their position of strength in today’s world and take steps to ensure that their labour is indeed able to lead to empowering effects for the weak. This is not just a hope. I rely here on Marx’s concept of humanism. For Marx, social relationships arise from relations of production and consumption, and positive social relationships are those that create genuine use-value, without coercion or instrumental use of others. Technologists are workers too, and I believe we are driven by these same desires of reclaiming our humanism. I strongly believe that sooner or later technologists will indeed see through the fog that often surrounds them and blunts their passion of taking deliberate action to bring about social good and only that through their labour. Collectives of technologists that can change their organizations from within, public spheres that connect technologists with end-users of their technologies, and new economic structures such as the commons, may hold the key to the way forward.

Finally, I argue that such a value-driven ethos for technologists can exist only within the morally grounded rules of behavior that democracy tries to create for society. Pluralism to listen to diverse voices, learn from them, and change one’s preferences based on these insights, is what drives democracy. For their own humanism, technologists have a role here too to build meta-social good infrastructures that strengthen democracy through pluralism and structures of accountability and transparency. I argue that participatory media systems such as those created by Gram Vaani, and the community media ecosystem in general, are crucial for this purpose. These systems enable deliberation and learning, and see the media as a tool in the hands of activists and communities to increase freedoms and democracy, and not as a mechanism for propaganda wielded by the powerful.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

And we at Gram Vaani are eager to continue working with all our partners in the space of social entitlements and rights for rural communities and industrial sector workers, and explore new directions in improving gender equality by creating women-driven community media platforms, improve natural resource management by making it easier for communities to demand relevant water conservation structures and adopt alternate land-use practices, and design more appropriate community and health-worker facing applications for public health systems that can put the power of data in the hands of the users.

We are eager to build a movement to ensure that technology becomes an unambiguous force of social good and transforms the world rapidly into a more equitable and fair ecosystem, capable of handling the grave impending challenges of inequality, exploitation, poverty, and climate change that we face today.

sincerely

Aadi

———————————————————————–

Given the enormous influence and control of technologies over our lives, an ethical enquiry into their development, use and ownership is of vital importance. This book provides an incisive account of how state and market-led technologies have exacerbated socio-economic and environmental injustice, and conversely, how technologies based on the ethics of plurality, diversity, power-based equality, freedom and participation can help the movement towards justice and sustainability. Seth’s call is not for rejecting technology, but for paradigm shifts towards more socially engaged technology and technologists.

— Ashish Kothari: Kalpavriksh, Vikalp Sangam and Global Tapestry of Alternatives

If you want to use information technology to make a positive difference in the world, then you need to read this book. Aadi Seth combines careful analysis of the interplay between technology design and socio-political processes with a wealth of practical experience to identify key challenges that efforts around IT for Good will always have to face.

— Andy Dearden: Professor (Emeritus) Interactive Systems Design, Sheffield Hallam University

Professor Aaditeshwar Seth has spent years developing technologies through Gram Vaani, a social enterprise delivering a voice-based social media platform in northern India. Based on wide-ranging scholarship and hard-won experience, he counters market values with an approach to social impact that takes ethics and socio-technical theories seriously. If you’re a technologist hoping to contribute to social good, this book will keep you honest!

— Kentaro Toyama: Professor, School of Information, University of Michigan

What comes out most importantly in the text is Aadi’s two-fold firm conviction – one, that a technological community committed towards social good is indeed possible; and two, that dividing lines across technologists and ordinary people can be bridged, and this is what he has argued for. I hope that the technological community engages with these arguments.

— Rahul Varman: Professor, Department of Industrial & Management Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur