by Vani Viswanathan

‘I dreamt of putting my children through school and taking care of my aged parents with the money I make,’ says Rakhi from Jamui, Bihar, who migrated with her family to Gujarat. Rakhi had to flee back to her hometown to avoid violence before she could earn enough, with fear and insult stinging her and dashing her hopes for her family.

Govind from Kanpur, who has migrated to Haryana, says wages are never paid on time, leave alone the fact that it is inadequate for the work done. ‘We are treated like animals,’ he says, ‘the locals always think they are much better than us.’

Stories like Rakhi’s and Govind’s abound in Bihar, Delhi/NCR, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh, where Mobile Vaani clubs are active in gauging the pulse of community members. We reached out to community members in the aftermath of the violence meted out on Hindi-speaking migrants in Gujarat after a migrant from Bihar was accused of raping a toddler in September 2018. Speaking to migrants and the discrimination and violence they face was among the first of our discussions on the status of workers and labour in India as part of a campaign called Shram ka Samman – Respecting Labour.

Who migrates, and why?

An estimated 9 million people migrated annually within India between 2011 and 2016, according to the Economic Survey of India, 2016-17. This figure is likely to include inter-state migration as well as short-term ‘circular’ migrants, such as those who only migrate during the lean agriculture season when they don’t have work that pays, and return to their villages or farms once sowing or harvesting season begins again.

The largest share of inter-state migrants come from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, totalling up to over 900,000 migrant workers, who often go to the relatively more prosperous states of the south and the west, including Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Maharashtra and Delhi. The Economic Survey 2016-17 found a strong correlation between state per capita income and migration: Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, with among the lowest per capita income, reflected high outbound migration, while ‘relatively more developed states’ such as Goa, Delhi, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka reflected net in-migration.

People’s reasons for migration reflect a resounding lack of jobs locally. Community members shared a variety of reasons – all to do with lack of jobs locally – for why they migrated.

Listen to Ajit Singh here.

Listen to Devi Kumari here.

Listen to Om Prakash here.

Listen to Dilip Kumar here.

The growth mismatch

Even as we tout increasing rates of economic growth in India, it has not been translating into enough employment opportunities in the recent past – Azim Premji University’s ‘State of Working India’ report shows that in the 2000s, a 10% increase in GDP results in less than 1% increase in employment, when in the 1970s-80s, even a 3-4% increase in GDP would result in 2% employment growth. In 2011-15, APU’s calculations showed that for a 6.7% Compounded Annual Growth Rate, there was only a 0.6% rise in employment. Unemployment has only been growing, especially among states in the north. The government-contested statistics from NSSO on the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS), recently published by the Business Standard, state that unemployment rate is a four-decade high of 6.1% in 2017-18.

On the other side of this statistic which the relative prosperity of the western and southern states belies is the lack of employment opportunities for the locals in this state. An analysis in the APU report of employment generation rates in both agriculture and non-agriculture sectors shows that it slowed in the key migrant destination states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Gujarat. This has led to resentment among locals, who find that they cannot get employment that matches their qualifications, a problem that especially states with high enrolment of young people in tertiary education has to handle. Madhvi Gupta and Pushkar write for The Wire on why the trend of educated but unemployed youth is an issue that India needs to pay attention to. Writing in the aftermath of the violence meted out on migrants in Gujarat, Rajeev Khanna discusses how despite its promises of growth for all, Gujarat has many young, unemployed locals who, rather than question their government, chose to incite violence against the ‘Hindi-speaking migrants’ who have ‘snatched away jobs’.

‘They use “Bihari” as an insult’

Ask migrant workers about how they were treated in their place of employment, and bitter experiences come forth in plenty.

‘Once they hear us speak, they know we are not from here,’ explains Manohar Lal Kashyap, who works in the outskirts of Delhi. ‘The company I work for doesn’t employ locals because the employers are scared of them… instead, we’re asked to do work that we didn’t sign up for, and if we raise our voices, we’re shown the door.’

Nitish Kumar from Gidhaur, who drives an auto-rickshaw in Mumbai, recounts the harassment he faced at the hands of officers at the Road Transport Office. ‘They slapped a random fine of thirteen thousand rupees on me, and I had no choice but to not pay it. They don’t do this with locals here,’ he says. Discrimination against Biharis is an everyday affair, he says.

Many who responded to our call for experiences on Mobile Vaani reported that they were treated without basic respect, simply for being Biharis or Hindi speakers. ‘Bihari’ was often used to indicate different levels of intelligence or sophistication.

‘“Bihari, come here!” is how we are commonly addressed. It is very disrespectful,’ rues Santosh Kumar Pathak from Munger. Ajit Singh from Jamui recalls experiences of being teased endlessly for no reason by his Gujarati colleagues, and complaining to his boss was of no avail. ‘He said that it would settle down in a few weeks, but that didn’t happen,’ he says, indicating that redress mechanisms are all but absent for migrant workers.

Rakhi shares how locals wouldn’t even let migrant workers sit next to them. ‘We’re always treated as outsiders and as workers. I lived in constant fear because I knew that if something went wrong, they wouldn’t hesitate to beat us up.’

Mahesh Kumar Yadav from Jamui wonders why, when migrants to Bihar are treated well, migrants from the state aren’t treated with respect wherever they go.

‘One person’s crime should not be used to paint a whole community,’ says Teknarayan Prasad Kushwaha from Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, in the days following the Gujarat episode. ‘The government and police forces should understand that migrant workers have left their homes behind only to earn and support their families.’

How family life gets affected

Most male migrants leave their families behind when they go to other cities or towns. Common concerns are about their safety in the destination, the irregular availability of jobs, and therefore, the inability to ensure that they can provide for their families in cities/towns where expenses are higher. Sonu Yadav from Gidhaur, Jamui in Bihar, for instance, says he gets 450 rupees for 8 hours of work. ‘How can I live with my family here, on this kind of money? The money is enough only for me to live here, take care of my travel, food and so on.’ When does he visit them, then? He only heads home for the few months when it is the farming season. Jitan Mahto from Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, has also left his family behind because he has moved to the city with a contractor, who demands many hours of work each day and penalises him if he doesn’t meet these numbers. ‘If I take even a few days off, I could lose my job,’ he says.

Leaving families behind can also lead to issues in accessing social welfare benefits. Jitan Mahto says that since one has to visit the block office to register for most of these benefits, it has been difficult for his family after he migrated to get these. Middlemen are there to ‘help’ such families, but they end up transferring the benefits to other families that aren’t eligible. ‘They ask for many documents,’ he says, alluding to the complicated processes which oftentimes women or the elderly – left behind in the village – are unable to navigate. Motilal Paswan from Muzaffarpur, Bihar, who has worked in Assam, Nagaland, Punjab and Uttar Pradesh, has been relatively lucky in this regard. He has managed to have his home built under the Indira Awas Yojana (now the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana), and his children and wife are easily able to access the public distribution system to buy essential grains and other groceries at government-subsidised rates.

The difficulties grow if someone falls sick – the migrant himself, or a family member. Sonu Yadav rues the lack of medical benefits from his employer, which means he has no option but to spend his meagre salary for treatment. Jitan Mahto, on the other hand, describes how when his child contracted malaria, he had to bring the child to a city hospital because facilities in the village were poor – and that meant a significant drain on his savings.

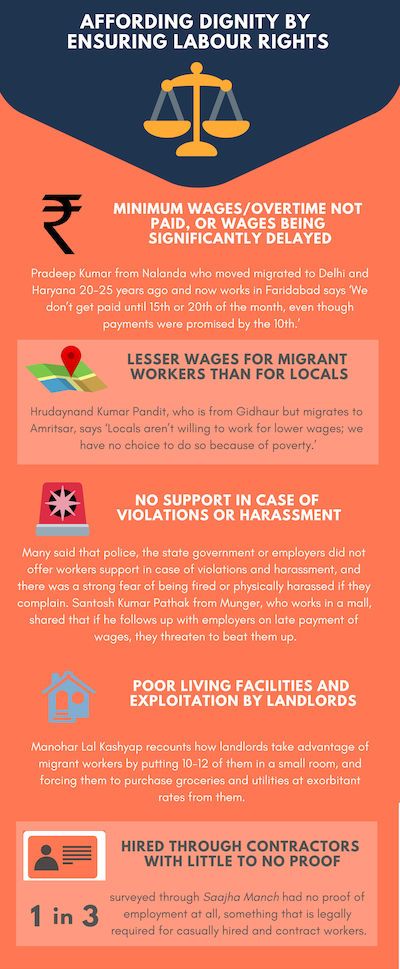

Affording dignity by ensuring labour rights

Beyond disrespectful and demeaning behaviour, migrant workers gave many examples of how basic labour rights weren’t met. Here are some issues that workers brought out on the Shram ka Samman campaign, some of which also came up in a survey in Delhi-NCR we did in 2018 through Saajha Manch, our platform for Hindi-speaking migrants across the country:

Here’s a glimpse into what community members voiced as steps that will ease the lives of workers:

- Strong demand for local employment opportunities, especially in Bihar. ‘Why would we go elsewhere if we had jobs here?’ is a common refrain from many workers who spoke to us.

- Cooperation between state governments to ensure rights of migrant workers are met and they are treated with respect and dignity. For instance, Rakhi says that the Bihar government must collaborate with the governments in Maharashtra, Assam and Gujarat to seek their support to migrants from Bihar who go there to work.

- Registration of workers leaving the state for work outside to track what’s happening, ensure payments and insurance are maintained. These are mandated in the Inter-state Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act 1979, but are routinely flouted.

That the Indian Constitution gives citizens the full right to move to and live in any part of the country was emphasised by many workers who shared their opinions on Mobile Vaani. And yet, violence against migrants is a recurring, common feature, as Indradev Chauhan from Jamui reiterates. With the country still in transition from being an agricultural economy to an industrial economy, labour and employment policies have to be mindful of both economic and social concerns. In our next article in this series, we will explore the role of agriculture in addressing the labour and employment crisis in the country.