WCRC Leaders Asia has carried a fantastic article about Mobile Vaani! Original link

Leveraging the high penetration of mobile telephones into rural India, a social tech company has given one of the country’s most backward regions its first social media network

By Swati Madan and Tulika Singh

in Jharkhand

Farkeshwar Mahato from Khedabeda village in Dhanbad district of the eastern Indian state of Jharkhand leaves a message on social media, calling on the administration for constructing buildings for Anganwadi centres operating without structures for over 10 years. No later than a month, tenders for construction of buildings for these state–funded basic health care and pre-school education centres are floated. It’s not long before children will not have to study in the harsh sun or walk a mile or two before they can relieve themselves and that too in the open.

Sounds like a tweet having gone viral or a post snowballing into a campaign on Facebook? Well, Mahato doesn’t know squat about Facebook or Twitter. He doesn’t even have access to the Internet – just like 93.3 per cent of India’s 833 million rural population. He just left a voice message on Mobile Vaani – a citizen radio-over-phone platform accessible to people across one of the India’s most media-dark zones. It is Gramvaani’s – a social tech company based out of IIT Delhi – answer to building a social media platform equivalent to Facebook/YouTube/Twitter for rural Indians.

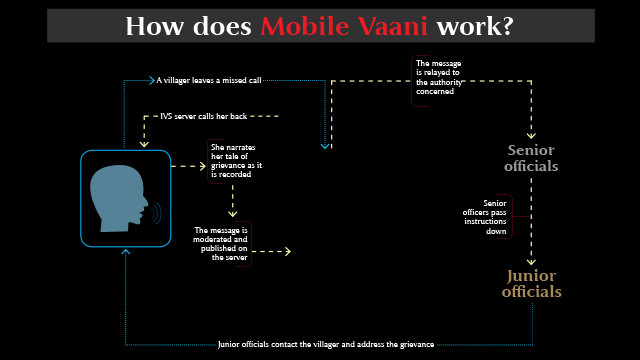

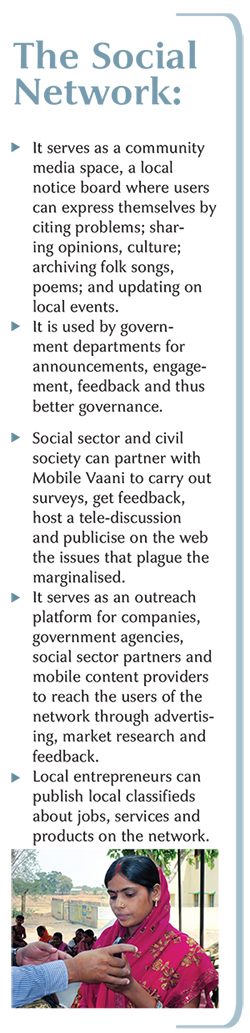

Leveraging the rapid penetration of mobile phones into rural India (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India pegs telephone subscription rates in rural India at 38.9 per cent), Gramvaani built an intelligent IVR (interactive voice response) system that is reachable by placing a missed call to the number 088000 97458 or a paid call to 01166030086. It allows people to leave a message or listen to messages left by others for free. These messages vary from local grievances to feedback on government schemes, updates on local events and culture, to discussions on state of health, education and infrastructure. Villagers can also tune into live awareness campaigns and post a comment.

“If it weren’t for Mobile Vaani, the likelihood of our children studying in shade or having access to proper sanitation would be rather dim,” says Farkeshwar Mahato.

Ganesh Matho from Giridih district in the same state had had to migrate to New Delhi for lack of employment opportunities in his state. Working on a measly pay for a caterer, he died under mysterious circumstances. The death of this 35-year-old migrant worker was not even reported by his employer. Barely getting by on the money he used to send home, his widow was left devastated with no source of income to provide for her. Her only recourse was the compensation of $2,500 or 1,50,000 Indian Rupees she was entitled to from her

Her repeated entreaties to the labour department were going unheeded when, V.K. Verma, a social worker, left a message on the very platform, pressing the district labour officers to help Matho’s widow get her due. Just two days later, officials from the department visited her house and ordered an inquiry. “I have never before witnessed a grievance being redressed so promptly and effectively,” says Verma.

Mobile Vaani’s flagship deployment in Jharkhand – an insurgency-hit, backward Indian state with a sizeable tribal population of 26.3 per cent (as per 2001 Census) – clocks about 1,000 calls per day and reaches out to more than 20,000 callers, giving voice to the hitherto voiceless. Users speak and listen to contributions over the intelligent IVR platform. Content is moderated locally and centrally and then published on IVR and the web. These inputs are connected to relevant stakeholders – government departments, NGO partners and social enterprise partners.

“The moment something is on social media, it spreads like wildfire. People start taking action. Seventy per cent of the population on the dark side of the digital divide has not benefitted from governance for long. But now, the Internet, which is not run by the government, has given people a say in the matters of governance. But these are families of five to six members subsisting on $33 or 2000 Indian Rupees a month. So the question was whether we could think of a solution – a social media platform for the folks at the bottom of the pyramid. While the government has been talking about getting this 70 per cent to the mainstream, we’ve actually brought them to the mainstream,” says Ashish Tandon, vice-president, business development and strategy, Gram Vaani Community Media Private Limited.

Jharkhand Mobile Vaani (JMV) has been actively carrying out campaigns on matters pertaining to, but not restricted to, gaps in the service delivery systems of various government schemes, lack of awareness on social issues and better understanding of agricultural practices. It ran a five-week-long ‘Close the Gender Gap’ campaign in partnership with Oxfam India in March 2013 to elicit people’s perceptions on gender discrimination so as to bring out suggestions on how to close the gap.

“In my career of seven years in the development sector, this is something entirely new in terms of ensuring last mile connectivity to the rural folks. I have visited some of the most remote regions in Jharkhand, places where there are no concrete roads for 30 kilometres, places where rivers and ponds dry up in the summer and places where villages after villages have been affected by mining and villagers have been evicted from their own lands. Apart from their struggle for survival, what these people need is a way to communicate their issues to the larger world and to the relevant stakeholders. This is where JMV plays a huge role,” said Sayonee Chatterjee, programme innovations manager, Gram Vaani Community Media Private Limited.

On August 16, 2013, Ravindra Kumar Verma from Leda village used the platform to point out the laxity with which health workers at primary health centres were going about their jobs. On August 31, the block development officer concerned was ordered to call a meeting of the workers and conduct an inquiry.

“Earlier, the doctors and nurses at the primary health centre in Simariya were pretty irregular. But since a complaint was made on JMV, they have pulled up their socks,” said Ravindra Kumar Verma.