In a collaborative effort by Gram Vaani, Magasool, IIT Delhi, IIT Palakkad, FES, GIZ, SUPPORT, and 4S teams, a series of consultations were conducted in Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha and Rajasthan to identify key socio-ecological variables that could effectively represent the challenges faced by communities and delve into the intricate issues surrounding commons resources and livelihoods dependent on them. This blog aims to shed light on the key takeaways from our consultations report and emphasize the importance of these aspects in shaping sustainable Natural Resource Management (NRM) plans.

[Socio-ecological consultation report]

Key Takeaways: Shaping NRM Plans

The consultations aimed to capture community and governmental efforts in water security, afforestation, biodiversity conservation, and the pivotal role of MGNREGA towards these. Our goal is to eventually develop a universally applicable socio-ecological action framework that integrates ecological and social parameters but is context sensitive at the same time to transform raw data into actionable insights for local communities.

Picture a tool that not only provides information but becomes a catalyst for informed decision-making at the grassroots level related to local restoration activities, ecologically sensitive livelihood opportunities, and market practices.

Socio-ecological variables: Insights from the consultations revealed the importance attached by communities to some key socio-ecological aspects

- Water resources: Communities urged for assessing the availability of water in dams, ponds and other water structures. This information is crucial for planning crops and various livelihood-related activities. Additionally, these insights play a vital role in developing effective plans for structures that recharge groundwater, aiming to prevent over-extraction and depletion of water resources.

- Climatic Dynamics: The evolving climate is a crucial factor in community resilience. For example, the irregular distribution of rainfall across different regions has a direct influence on agricultural productivity and these rainfall disparities can also lead to variations in soil moisture, affecting crop yields and planting seasons. In regions where rainfall is abundant, there may be a risk of soil erosion and nutrient leaching. Conversely, in areas with insufficient rainfall, drought conditions can jeopardize crop production, leading to food insecurity. Understanding these disparities empowers communities to adapt and prepare for environmental shifts and build resilience.

- Soil Health: The use of chemical fertilizers has had detrimental impact on soil health and raised distress with an increase in agri-input costs. Knowledge about changes in soil health can equip communities to adopt sustainable agricultural practices, promoting both environmental health and robust livelihoods.

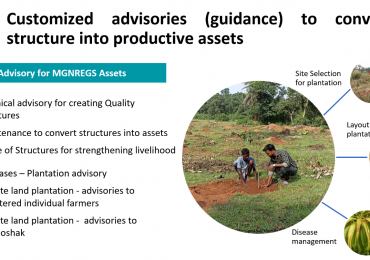

- Land Usage: Land, the foundation of agricultural endeavors, needs better planning especially for restoration of degraded lands to aid strategic decisions like plantation planning and rotational grazing. Armed with this information, communities can optimize land usage for sustainable practices.

- Land & Resource Ownership: Effective planning of NRM assets hinges on having a clear understanding of land and resource ownership. Understanding the land and resource ownership information can ensure fair distribution of resources, promoting social and economic equity within communities. Furthermore, it can help guarantee that the implemented plans are not only context sensitive but also tailored to meet the specific needs of all communities.

- Biodiversity Index: Communities expressed a pressing need for a biodiversity index based on tree species in their forests. Scarcity of fruit-bearing trees leading to wild animal attacks on crops emerged as a concern. Forest officers stressed the importance of tracking tree species density and health to predict events like forest fires and use these indicators to make better plans for preservation of biodiversity and mitigation of potential ecological threats.

- Government Scheme Intersection: Different kinds of NRM activities are funded under different schemes, and requires facilitation support to enable communities to get guided towards the appropriate schemes.

Ecosystem Perspective: The consultations highlighted the crucial need to shift from isolated resource approaches towards an ecosystem perspective. Recognizing the interconnected nature within an ecosystem emerged as a key takeaway, emphasizing the interdependence of various socio-ecological variables. This perspective urges a holistic understanding of how changes in one aspect may have a broad impact across the entire system. For instance, an emphasis to address biodiversity concerns in forests may require communities to diversify their livelihoods towards agriculture, and require an integrated water management plan that can sustain both water needs in forests for rejuvenation as well as for irrigation in cropped areas. The ecosystem perspective thus encourages a comprehensive approach to NRM by acknowledging the dynamic relationships between different components.

Community Engagement: The importance of actively listening to local community experiences also came out prominently, to ensure that NRM plans are tailored to address local needs, and foster a sense of ownership and commitment to conservation efforts. The unique perspectives and traditional knowledge held by communities positions them as crucial stakeholders in the sustainability journey.

Based on the consultations conducted, a comprehensive set of 80+ socio-ecological variables were developed, spanning Agriculture, Water Bodies, Forests, Pastures, Social aspects, Climatic variables, and Welfare considerations. Among variables that can be obtained from remote-sensing data, the most prominent ones were related to rainfall deviation across the years, regular time-series for runoff and groundwater recharge, surface water availability, and agricultural metrics such as cropping intensity, and changes in land use and forest health. Not all the variables can be obtained through secondary data such as from satellite imagery and other maps though; primary data will also be required for a wide range of variables such as on agricultural elements like market linkages to socio-economic aspects such as land ownership, livelihoods, and education. Further, community feedback will be needed to appropriately weigh different ecological considerations based on the context, such as variables related to forest and pasture dynamics, invasive species, and extreme weather events. Cultural elements such as sacred groves and socio-demographic factors including caste distribution and women-led households will also need to be modeled. Economic variables, political connectedness, and welfare scheme utilization were also examined, to build a holistic understanding of a region’s dynamics. An extensive survey has been prepared to collect such data.

Next step: Build Digital Public Infrastructures

Based on the insights, we have begun working on the CoRE Stack (Commoning for Resilience and Equality), a digital public infrastructure for climate adaptation by rural communities. This stack enables an open-access co-creation network, fostering innovation and scalability of digital technology solutions for ecosystem sustainability. Currently, the first tool being built on the CoRE stack, Commons Connect, stands as a robust resource for community volunteers, providing them with a profound understanding of the landscape and socio-ecological dynamics. Offering detailed insights into groundwater and surface water bodies, as well as agricultural practices, the tool empowers them to effectively illustrate and communicate these complex dynamics to the community. Read the first quarter update on the CoRE stack.