GRINS was a finalist in the Ashoka Changemakers’ 2011 competition. Zahir gave a detailed interview on how community radio stations all across India are using GRINS. Original source here

Just for GRINS: An Interview with Gram Vaani’s Zahir Koradia

A large proportion of mobile phone users in India prefer voice communication to SMS or written interactions. Why? Because literacy rates affect how users interact with mobile quite a bit.

Clearly, if you’re illiterate—and more than 450 million people in India are—SMS offers little value. Community development institutions and social enterprises in the Indian subcontinent are turning to voiced-based technologies to connect users to their world.

One such example is Gram Vaani’s flagship automation system, GRINS, an entrant in the Changemakers Citizen Media competition, supported by Google. Gram Vaani is a participatory media organization that has built a nationwide network of community radio stations, proudly broadcasting on FM frequencies; telephony applications allowing the social sector to better engage with the public; and a voice-based rural news serviced powered by the mobile phone.

GRINS helps Gram Vaani realize its mission to develop solutions that give people a greater say in community matters by facilitating engagement between everyday citizens and established institutions like the government and development organizations.

Changemakers recently spoke with Zahir Koradia, Gram Vaani’s lead developer, to find out why the venture has been so successful—even landing a $200,000 grant from the Knight Foundation in 2008. (Hint: Gram Vaani is more than a single, popular mobile app or affordable tech feature—it is an entire network of action, information and accessibility to communication services.)

Changemakers: What was the big idea in 2008 that got this project started?

Koradia: The whole idea at that point in time was to try to see how we can build technologies to enable community radio stations in India. We weren’t really looking at anything beyond that, we were just saying, “Let’s look at the community radio movement in India and let’s see what we can do for (the poor, marginalized populations.)”

Our timing was just right, because community radio stations were just starting to open up. The government of India had started giving out licenses in 2006, and, in 2008, we were seeing the first couple of radio stations operated by NGOs.

We were just lucky, you know? We were just getting into the community radio movement at the right time.

Changemakers: Can you give a little background about the community radio movement?

Koradia: Before 2006, there were a few experiments by NGOs and community media organizations in India to create community-led programs where people spoke about the issues they themselves were facing. These basically pushed the government to say that community radio in India can work—here’s the proof.

In 2006, the government allowed NGOs and educational institutions with three or more years of experience to set up community radio stations. It was a big, drawn-out process where organizations had to apply, go through several ministries, and have to wait anywhere between six months to a year-and-a-half to attain a license, which grants you permission to broadcast on an FM frequency.

There were entities that got into place to provide stations with equipment like mikes, mixers, and broadcast equipment, but in spite of all these options, people would usually end up using a simple media player for broadcasting their content. And that’s where Gram Vaani actually fits in.

What we noticed was that the equipment that would allow stations to do that were extremely expensive in India. What we did was begin working with relatively inexpensive recording device that connects to a computer, and built an interface allowing station staff to receive calls and put them live on air with the click of a button.

That way, they wouldn’t really have to mess around with audio cables, or hardware switches or anything. The idea was not to just allow them to improve community participation, but to make it easy for them to do so.

Changemakers: The hardware technology is affordable, but your software offering, GRINS, is free to download, install, and use. The only charge is the cost of training and support?

Koradia: That’s right. We’ve sort of evolved. About two years ago, we were looking at ways of selling the automation system, but we realized that the only way we’re really going to have an impact is if the service is free; we’re only charging for basic training and installation costs, which basically cover our costs.

Changemakers: Gram Vaani makes community radio possible and affordable—that’s clear—but what does community radio offer people, who, in many cases, are living in poverty in rural towns?

Koradia: Instead of actually giving a high-level answer, the best way to explain is to give examples. There’s one radio station in Central India called Radio Bundelkhand that started out in 2008. They have their own folk music called Bundeli, which was dying down, so the community ran a regional version of American Idol called “Bundeli Idol,” a competition that invited anyone to record a song in the studio and have it played on the air.

Recordings were filtered by the public, who could call in and vote for their favorites, and a judge was eventually hired to determine the winner. The people loved the idea; they started telling their families and friends about it. There was a sense of pride being able to say, “I was on the radio.”

The program has actually revived the culture of Bundeli songs — after the competition, being able to sing Bundeli songs or play the folk instruments in considered cool, as opposed to passé earlier on.

And the station now has a repository of good Bundeli songs for community broadcast. Radio Bundelkhand is in the process of launching the second iteration of “Bundeli Idol.”

That highlights the cultural aspects of community radio, but there’s a tangible example of how it has made a difference in the quality of life of the people. India passed the Right to Education Act (RTE) that says all children between the ages of 6 and 14 must receive a school education.

There’s a radio station called Radio Namaskar, based in Orissa in eastern India, which broadcast a description about the act and asked the community to share information about children they know who aren’t attending school. They set up an answering machine system, using our GRINS automation system, and people called in, which then led to meetings and discussions between parents, children, and the local authorities to find ways to get them in school. Over a period of four to five months, they were able to reduce the number of children not attending school to zero.

Changemakers: That’s amazing.

Koradia: To me, that’s a dramatic achievement, and a testament to the power of broadcasting, the right to information, and being able to interact with the community.

Changemakers: How are the majority of people using the technology? Is it mostly cultural? Political?

Koradia: What we’ve noticed is that all these stations that are using GRINS are actually very different in nature—they all have their own specifics. But if I were to try to generalize it a bit: about half the stations try to interact with community, in whatever thing is being discussed—local issues.

Those are usually things related to traffic situations, or the availability of civic facilities, or things related to elections, or the difficulties that different sections of the population are facing. At the highest level, it’s really specific to the locality in which the station is located; generally, GRINs allows a high amount of interaction, which is something that was not possible before.

Changemakers: Gram Vaani also launched a mobile news service, Jharkand Mobile. How is that going?

Koradia: The mobile news service is actually being used in two places: the first is in the state of Jharkand in (eastern) India. We tried out the service with a lot of social activists on the ground; the whole idea was that people could call in and listen to news items that were posted on the system, and even record news items by simply leaving a voicemail.

We had several staff members validating the recordings and moderating the news tips before making them available to the public. It’s like a crowdsourced news service, if that’s the way you want to put it.

Changemakers: Which is kind of cool, because you get access to both national headlines as well as local news stories—made available before the mainstream media can get a handle on them.

Koradia: Our purpose for crowdsourcing news was slightly different. What we noticed was that there are areas where media organizations don’t do their tasks well.

It could be because it’s not really profitable for them, or because authorities make it hard for them, for whatever reason. In the state of Jharkand, we believe it’s the authorities that make it hard for news organizations to collect news.

In Afghanistan, which is another place where our service is running, the scenario is different. The difficulty is that there aren’t enough media organizations, and those that do exist don’t have the capacity to meet the news or information needs for everybody in Afghanistan. Our service adds to reporting capacities, so to speak

Changemakers: Gram Vaani has been around since 2008 and grown quickly. Where do you see yourselves going in the next five years?

Koradia: Gram Vaani is actually looking at building tools and platforms that will basically allow two things. First, increase the transparency of government services and their provision to citizens.

Second, provide a platform where citizens can come together and voice concerns or suggestions for government authorities—to bring out the kind of needs the communities have, and give governments something they can tap into.

We’re also working on “We Act,” which is a tool that we’ve built in conjunction with local municipal authorities in Delhi. It allows people to call in and report garbage collection issues, or broken roads, or any other missing civic amenities.

Those complaints are taken up and made available on a website. We tie this into the internal processes of the local government, so that the complaints can be delegated to the right people and addressed properly. The whole thing fits into the big umbrella of enabling accountability among government authorities, transparency, and enabling citizen participation in activities that government addresses.

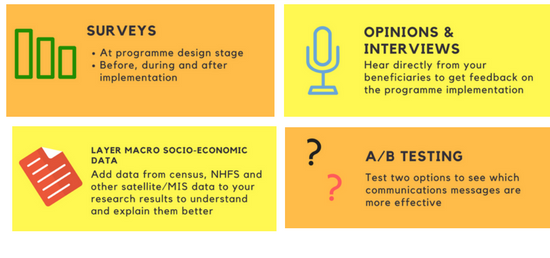

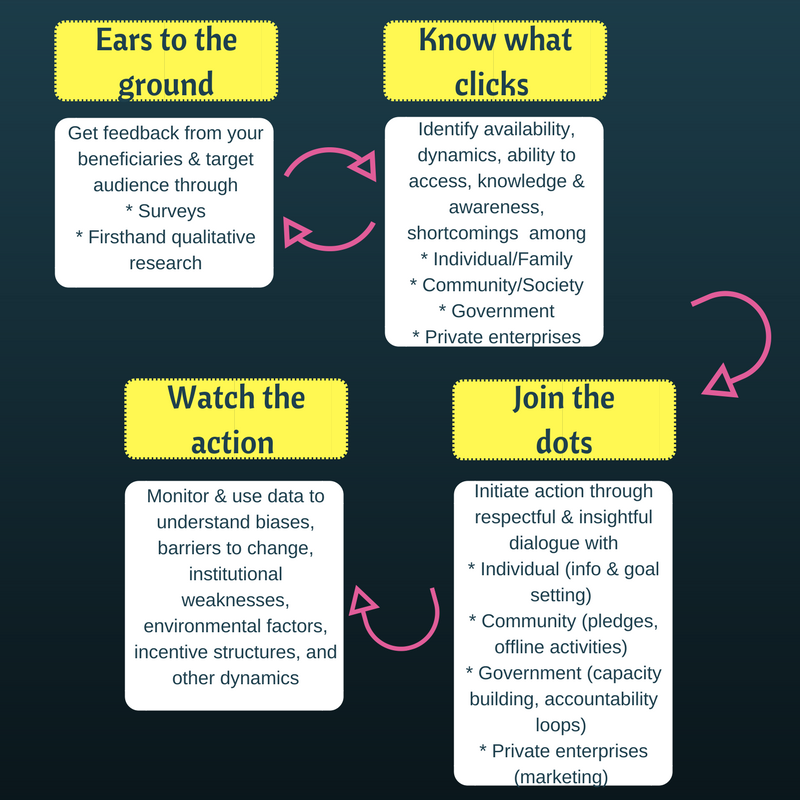

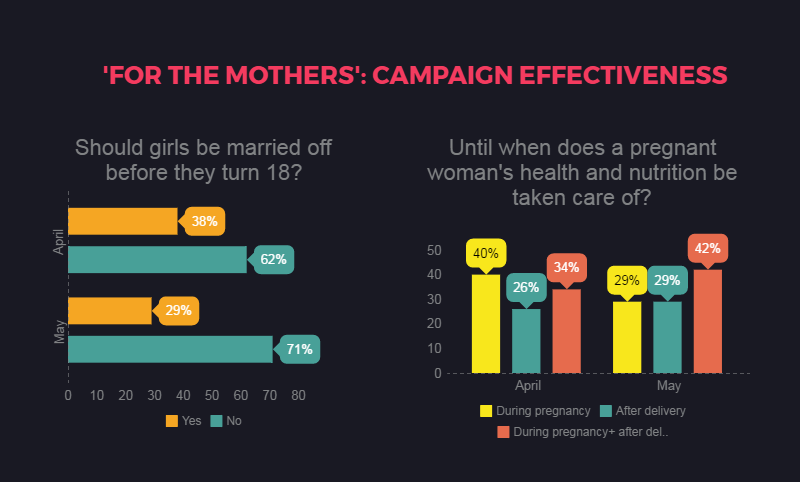

Comparing the effectiveness of different strategies

Comparing the effectiveness of different strategies