In the weeks since the Kisan Long March, we at Mobile Vaani reached out to farmers in Bihar to ask what were the biggest issues they faced and what their demands of the government would be.

Unsurprisingly, most of the farmers talked about the Minimum Support Price, the MSP. Of how it is not sufficient, or of how it is meaningless outside the few government procurement options which have to buy farmers’ crop at MSP, or of how it extends to far fewer crops than it should.

The manifestations of MSP not being an efficient system was mostly seen in terms of whom farmers sold their harvest to, especially in the case of paddy and wheat, which are the crops procured the most by the government each year. As a part of the country’s rice bowl, Bihar is expected to be a significant contributor in paddy procurement each year, and Primary Agricultural Credit Societies, or PACS, are highly promoted by ministers in Bihar as a one-stop, credible venue where farmers can sell paddy or, recently, wheat.

No wonder, PACS came up often when farmers who spoke with us through Mobile Vaani discussed the issues they are facing. PACS is high on visibility, with government leaders ranging from the state’s Chief Minister to the Deputy Chief Minister to the cooperative minister urging farmers to sell their crop there and promising strict action should PACS fail to deliver.

Keeping with farmers’ concerns, we also circled back with officers working at various capacities in PACS centres or at the block level.

What are PACS?

Primary Agricultural Credit Societies, of which Bihar has 8,463, are farmer-members-operated cooperatives that are given credit by cooperative banks (funded by state governments) to help farmers borrow money for capital improvement or to tide through losses, as well as a one-stop shop for high-quality seeds, fertilisers and other inputs, and most importantly, as a government-authorised and accountable venue for selling paddy and wheat. Upon procurement of the crop, especially in the case of paddy, it goes to the Bihar State Food & Civil Supplies Corporation, and then on to the Food Corporation of India, who direct it to the Public Distribution System. Payment is expected to reach the farmer within 48 hours of selling the crop at PACS, and the system has recently been digitised to make it easy for land-owning farmers as well as sharecroppers or tenant-farmers (those who farm on leased land) to sell their crop without difficulties related to producing documentation.

While farmers have a litany of complaints regarding PACS and its functioning, speaking with PACS officials and block officials reveals that these farmer cooperatives have struggles of their own to surmount before they can pass on benefits to their fellow farmers. The rest of this article discusses farmers’ opinions and experiences related to PACS, and responses by PACS officials to these.

Ground realities: PACS, procurement and payments

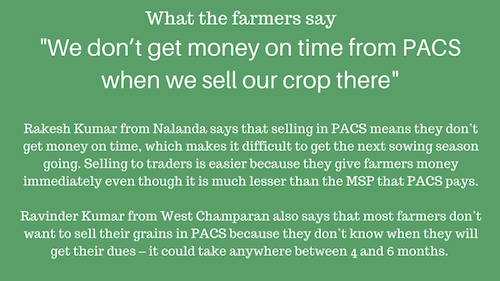

Listen to Rakesh Kumar’s opinion here:

Listen to Ravinder Kumar’s opinion here:

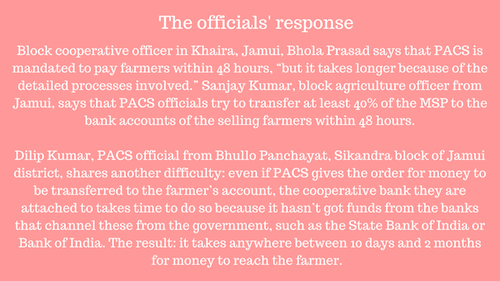

Listen to Bhola Prasad’s opinion here:

Listen to Sanjay Kumar’s opinion here:

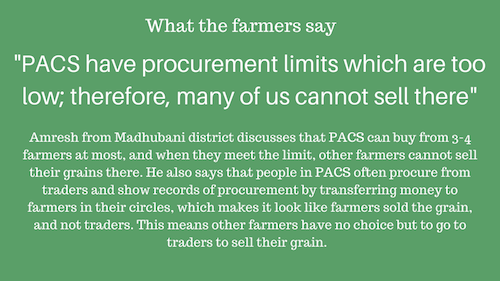

Listen to Amresh’s opinion here:

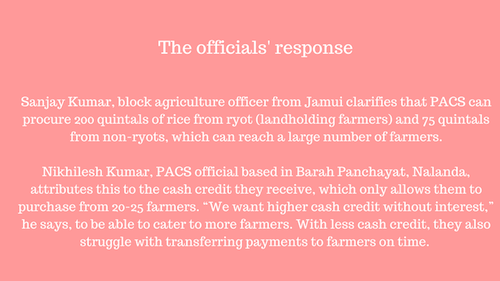

Listen to Nikhilesh Kumar’s opinion here:

Another issue that farmers did not bring up, but was discussed by Arun Kumar, PACS official of Khoksha village, Khatiyama panchayat in Nalanda district, relates to the moisture content of the paddy that can be procured. The limit is 17%, but the content of moisture in most grains is higher, which means farmers whose crop don’t meet this criterion have no choice but to sell to traders. There have been several discussions on raising the moisture content criterion in the state, as paddy and wheat grown in Bihar are typically of a moister variety.

Listen to Arun Kumar’s opinion here:

Listen to Manohar Singh’s opinion here:

Listen to Ram Kumar Prasad’s opinion here:

Listen to Shivanth’s opinion here:

This requirement for non-landholding farmers mentioned by Sanjay Kumar seems to have been in place since November 2016, as this news report from The Times of India shows.

Where gaps need to be filled

We see several gaps when it comes to what PACS is meant to do and how it serves farmers, especially small farmers.

The biggest gap seems to be in communication. Many farmers don’t know when they can go to PACS, or that even tenant farmers can get on to the PACS system by registering themselves with some easy-to-obtain documentation. Chandeshwar Ram Chandu from Madhubani district mentions how during awareness camps that the state government mandates are held in different blocks, party workers just bring their cronies to show attendance and farmers who need the information the most end up not knowing about government schemes or other important announcements.

Our biggest learning from running Mobile Vaani is the power of the mobile phone that can be leveraged for hyperlocal communication. For one, projects run on Mobile Vaani demonstrate that it can easily be used to make people aware of PACS’s policies and its functioning, as we have done with many areas related to agriculture. Additionally, PACS can make use of ICT systems to inform its members and other farmers in its catchment area on details such as the MSP and when procurement is expected to happen through a simple SMS system. This will help improve transparency, as has been successfully implemented with the public distribution system in states such as Tamil Nadu and Chattisgarh[1], where people can know whether the stocks claimed by the ration shopkeeper are legitimate.

Funding crunches defeat the purpose of PACS, as they do not have sufficient working capital to pay farmers without having to wait for funds to come to them from their associated banks. This issue is also seen in the broader space of Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) – legal entities formed by farmers to facilitate financing and disseminate information about the market/technology/inputs, among other things – even though several vehicles finance them, such as National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development (NABARD) and the Small Farmers’ Agribusiness Consortium (SFAC). There needs to be a bigger, concerted move towards lending more to these institutions, directly to the FPOs/PACS, or through these vehicles.

Finally, delays in payment transfers seem to be a common issue among several government schemes, notably the NREGA[2]. Aadhaar verifications or cashless innovations have not been effective in these circumstances, as they only compound the matter further – such as by payments being stopped because spellings in bank accounts and Aadhaar cards don’t match. As well as setting up a separate credit facility that can directly release verified payments quickly – as described in the previous paragraph – another solution that can be explored is to create sufficient buffers at different points at the state level so that these cushion any delays that happen in state vehicles sending funds to these organisations. This way, payments will go on time to the farmer, and credit will flow to the required buffers once it comes through.

An overall strengthening of the functioning of MSP can perhaps reduce farmers’ reliance on PACS by offering more avenues where farmers can sell their crops. Last year, CPI (M) rooted for the idea of Right to MSP, as well as an annual review of MSP that will offer a higher rate for farmers.

Farmers who shared their thoughts with Mobile Vaani were disappointed with the implementation of many schemes even as they recognised that successive governments have been trying various ways to improve farmers’ lives and strengthen agriculture. With protests – and suicides – by farmers only increasing in frequency and intensity, it remains to be seen when half of India’s workforce will get its dues.