Since I wrote my first blog about my short-term placement in the John Lewis India Sourcing Office, I’m now several weeks smarter about the world of retail sourcing and how we might work together with retailers to deliver development results.

A world of retail expertise

This has been the first time in years that I have spent time with an organisation whose primary purpose is not international development. It is obvious, but worth saying, that people who work in retail know a wealth of things I’ve never recognised as valuable – from the detail of how a product is made to the specialisms of producers in different countries and towns; the norms in commercial negotiations, such as minimum order quantities; the history of each supplier’s relationship with John Lewis (JL); the detail of what has sold well, as well as future trends in own brand collections and design styles. They understand their customers’ expectations on quality and price. They know their market position and market share, and have a sense of what other companies are doing and which personalities are moving jobs, in both their UK competitors and comparable companies in America or Europe.

John Lewis home ware products. Picture: Karen Johnson/DFID

Buyers and merchandisers are driven by short timescales, to meet the demands of 2 seasons a year. With ever smarter technology, the pace is speeding up, as customers increasingly expect instant service and endless product availability, driven by electronic innovations and online shopping. The John Lewis Partners I’ve met clearly care about the social and environmental contribution that good business can make, but most have busy jobs that don’t include knowing much about international development.

Sourcing from good suppliers

In this fast-paced retail world, corporate responsibility and quality assurance teams are the people who look out for the firm’s social and environmental impacts. They define ethical requirements for suppliers, spelt out in responsible sourcing codes, with compliance checked through independent audits. Responsible retailers like John Lewis manage product quality and social standards by sourcing from a small number of suppliers and nurturing long-standing relationships with firms that supply them. In the chain of sourcing relationships that link suppliers and retailers, people working on corporate responsibility seem to have a clear sense of where the biggest social and environmental risks lie.

I visited a home textiles factory that is a direct supplier to the India Sourcing Office, where the head of production explained that a large part of his costs are incurred in buying textiles sourced from other suppliers, but these mills are highly computerised and automated. In contrast, hundreds of employees do the cutting, stitching and finishing stages of production that his factory carries out, and getting standards right there will do most to protect workers.

Checking on suppliers’ suppliers

Everyone at JL seems to agree that a system based on compliance audits is not the smartest way to check standards in their second and third tier suppliers – there would be too many firms, and audits would be too expensive and time-consuming. But the retail world has become very used to checking social and environmental risks through compliance audits and it is early days in the search for new approaches. As I reflect on what I’ve learnt, I think it might be a good idea for DFID to work with those retailers who feel accountable for development risks at all tiers in their supply chain. DFID could help retailers assess and document these risks, especially in complex supply relationships, and ensure that new thinking is widely shared with other retailers.

Introducing smart innovations

The John Lewis corporate responsibility team also makes proposals to the John Lewis Foundation for grant-funded projects that help the local community. For example, they work with Cotton Connect to train Gujarati farmers to increase their productivity through better environmental practices in their cotton growing. What strikes me as particularly smart thinking is that 1 of John Lewis’s biggest suppliers in India now buys cotton from these producers and uses it in a range of bathmats on sale in John Lewis stores.

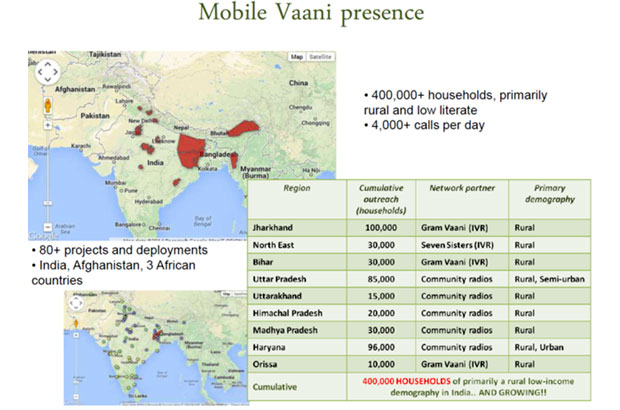

I wonder about other smart innovations – like those that use the power of mobile phones to improve poor people’s lives. India leads the way in electronic communications and I’m impressed with the organisations I meet. Could DFID help introduce retailers to digital innovators that are development specialists?

For example, Gram Vaani uses mobile phones to involve people in their local community and link them to services, through a social network platform called Mobile Vaani. A retailer like John Lewis might convince its best suppliers to do new things to involve their ‘community’ of workers, by introducing factory managers to this sort of digital innovation for development.

Bringing it all back home

All too quickly, my bags are full of my wonderful Delhi shopping finds and my head is full of ideas from my brief experience in the other side of retail. I’m grateful to all at John Lewis and DFID who made my short-term placement possible. I’ve seen how retailers care about the contribution they make beyond their commercial performance.

If we are smart, we can find ways to work together that are innovative, and build on how each of us work. If we get it right, we should jointly be able to deliver greater benefits for economic development and poverty reduction.