- An anganwadi worker says that food grains received in the centre haven’t been distributed to children and mothers it serves.

- Over 5,000 farmers haven’t received their insurance pay-outs from the government.

- A villager has been desperately trying for seven years to transfer land ownership from his deceased father’s name to his name.

- An illegal alcohol shop refuses to shut down despite complaints from neighbourhood residents.

What is common among these three stories from different parts of Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh, is that community volunteers associated with Mobile Vaani helped mobilise community action to resolve these issues.

And this is an idea that we believe has tremendous potential to be scaled up: having organised and trained community volunteers leverage simple technology to help people in far-flung, media-dark parts of India to have their grievances heard and issues resolved, create dialogue about social norms that are taken for granted and policies whose implications are hard to understand, and contextualize the use of technology for local needs.

The nuts and bolts of how it works

Operating in 25 districts across Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh, Mobile Vaani (MV) uses a simple IVRS technology to present locally relevant, multi-stakeholder information and views to nearly 100,000 users each month.

Users can listen to information related to social issues (such as on maternal health, early and child marriage, etc.), government schemes and local news, as well as record their opinions on these topics and share grievances related to their communities or their families.

Supporting this system is a network of 200 community-based volunteers and reporters, who are trained to report on locally relevant matters, publicize the MV platform and catalyze community action to solve local problems by bringing issues to the attention of relevant stakeholders. These volunteers are organized into clubs that operate at the district level and take ownership of their local MV platforms. They are responsible for building up the community user base, understand the needs of their communities, and support them in solving problems. Today, there are 13 such clubs across the 3 states in which MV operates.

There are several ways the volunteers ensure accountability and issue resolution: they forward messages from the MV platform to relevant local stakeholders to escalate problems and bring attention; they attend open-house events organized by local officials and politicians and take a commitment for assured action; they collate information through surveys and mobilize support through petitions which are shared with stakeholders to initiate systemic changes, they work with community leaders to hold local events and campaigns to questions social norms, and they train people by identifying relevant use-cases for new and empowering technologies like digital payments and various Internet platforms.

All this action is predominantly offline, undertaken in-person, which has been our most important learning on how technology platforms need to be supplemented with people.

Image: Dipanjan Chakraborty[1]

Empowering community volunteers: The next step

Mobile Vaani envisions strengthening the local clubs into true community institutions that can represent their community’s interests to governance stakeholders and lead to positive actions and resolution of community members’ issues.

This combination of community-level action by volunteers from the community who are empowered through far reaching technology platforms has the potential to be a one-of-its-kind citizen engagement and bottom-up media platform that spurs community action.

We believe that media should not stop at collecting and providing credible information, but should go further to ensure that the information leads to change.

Why are such decentralized institutions important?

Decentralized – local, for-and-by-the-community – institutions have been demonstrated as making the difference in strengthening state accountability and ensuring government services efficiently reach the people they are to benefit.

Decentralized collective action in Tamil Nadu in the 1970s forms the core of S. Vivek’s book ‘Delivering public services effectively: Tamilnadu and Beyond.’ Vivek argues that basic public services such as schools, child care, mid-day meals, public distribution and public health function remarkably well in the state, and are much better than other states in the country[2]. He attributes much of this to decentralized collective action that rose in the state in the 1970s, demanding accountability from local governance officials[3]. Vivek believes that these movements laid the foundation for a strong policy focus on delivery of public services that continues to this day.

Shifting the scene to present-day India, Dipanjan Chakraborty[1], a PhD candidate at IIT Delhi, analyzed the functioning of centralized helplines (phone and web-based) created for people to report grievances related to government schemes. Several issues were identified in the functioning of these helplines: people weren’t able to access/use them and collect the information required to file a complaint, they felt intimidated about speaking with a government official and often, didn’t know how to track the progress of their complaint. Most importantly, the helpline operators had low accountability to the people to attend to their grievances. Although a vibrant civil society exists in the country attempting to help citizens represent their concerns to relevant local stakeholders, these civil society members are cut off from centralized helplines.

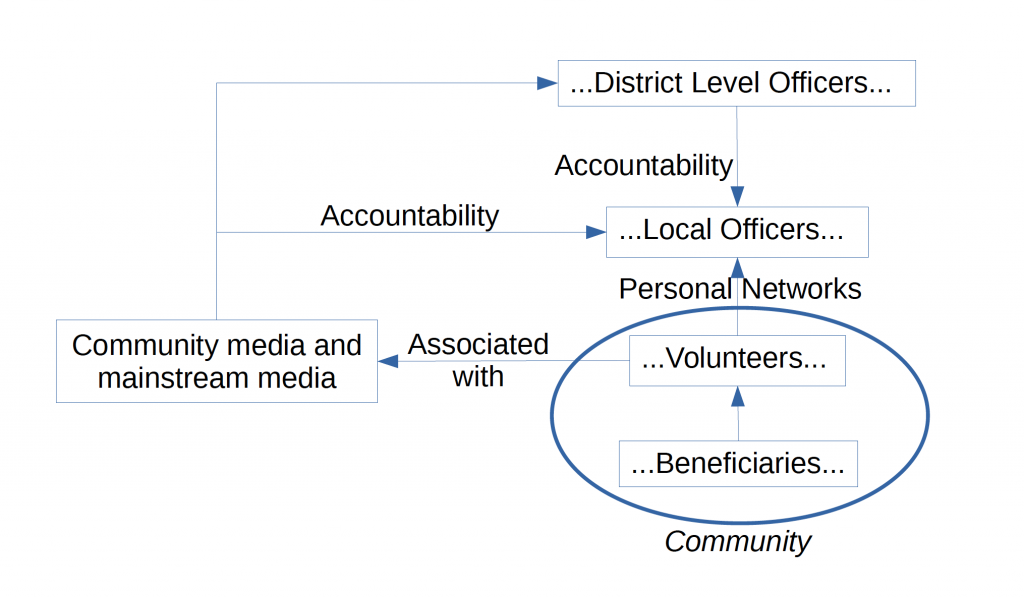

The authors, based on a pilot with Mobile Vaani, have noted several ways by which civil society members are more empowered to help with issue resolution: their personal contacts with relevant local stakeholders, their influence at the local level and their ability to pull in media to put pressure on stakeholders for resolution.

Noting that the government recognizes the importance of civil society organizations in grievance redressal and information sharing, the authors recommend that a civil society layer of technology should be added to the centralized grievance redressal process, so that these civil society members are formally brought into the process. In essence, technology will add decentralization to a system that might otherwise be distant and disconnected from the very citizens it seeks to serve. India has an extremely strong civil society and culture for social work, who can contribute even more effectively for their community’s development with the help of a localized community media platform.

The Mobile Vaani community institutions model

Mobile Vaani envisages that its clubs will be converted into community based institutions that function along the following lines:

- The organization will have members from communities (who join by paying a nominal fee), and will be run by officials elected from and by the membership base.

- Sponsorship will be obtained for non-commercial activities such as promoting relevant government schemes, running membership drives, organizing community events, consultations with local stakeholders, etc.

- The revenues from such projects will be used towards covering costs like institution building, community mobilization and human resource, among others, thereby ensuring financial sustainability.

- Gram Vaani will support in setting up the community organization, provide technical, financial and capacity building assistance, and help with procuring projects for financial sustainability.

Activities that these organizations can engage in include reporting community level issues (such as implementation of schemes, infrastructure gaps) and individual grievances, bring together communities with local stakeholders to resolve community issues, improve accountability of local governance processes (such as ensuring Gram Sabha meetings are regularly held), develop local events and campaigns on social issues, sharing good practices on agriculture and finance. We believe that if communities are happy with the community organizations’ work in representing their concerns and the community, they will support, and contribute to, its functioning.

Listen to some recordings of Gram Vaani impact here:

Anganwaadi grains are distributed after MV intervention:

Land ownership transfer becomes transfer after news appears on MV:

MLA of Gomia, Kasmar (Jharkhand) talks to Mobile Vaani about giving farmers their due insurance payments:

[1] Dipanjan Chakraborty, et al, “Findings from a Civil Society Mediated and Technology Assisted Grievance Redressal Model in Rural India”, Accepted at ICTD 2017.