Not yet, say results of a Mobile Vaani survey conducted in Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh.

Over time, the purported agenda for demonetisation shifted from capturing black money to putting India on a firm road towards cashless, accounted-for transactions. Phone payment apps from start-ups, corporates and banks rallied on this war cry and began tweaking their products to be made available to a larger base of the population. The Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM) mobile phone application, for instance, has been hailed for its user-friendliness, and the practicality that one doesn’t need a smartphone to use the app and its ability to bring millions under the net of cashless banking simply through a phone number linked with a bank account.

While this signals a good move for a country that is disproportionately dependant on cash, India is miles behind being ready for cashless payments in terms of infrastructure, availability of merchant-ready payment systems and biggest of all, people who are literate about any form of cashless payment and are willing – and able – to use it.

In the 100 days since the PM announced the withdrawal of Rupees 500 and Rupees 1000 notes from the market, much has been said about notebandi around the country. Mobile Vaani has been collating responses from Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh about demonetisation and its impact on people. This report presents some key views and statistics based on a survey[1] and content analysis of comments left by people on the Mobile Vaani platform, with a focus on knowledge and readiness among people to go cashless.

Who did we talk to?

The survey and content analysis are based on listeners of Mobile Vaani in various parts of Bihar, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh. The typical respondent is male, less than 30 years old, and has studied at least up till class 12. A majority of them are likely to be unemployed, with a cash inflow of less than INR 5,000 a month; most of them don’t own a TV or a radio. However, most of them own mobile phones and a bicycle. The respondents of Bihar and Jharkhand were very likely to own cultivable land.

First, what is cashless?

Indeed, the idea of a cashless transaction is in itself baffling for several survey respondents. As Bipin Kumar from Munger district in Bihar discusses[2], “India resides in villages, with many villagers being uneducated. The move towards cashless payments is an imitation of the West, where most of the population is educated. By pushing cashless, digital payments in the country, all the government has done is to make life difficult for villagers.”

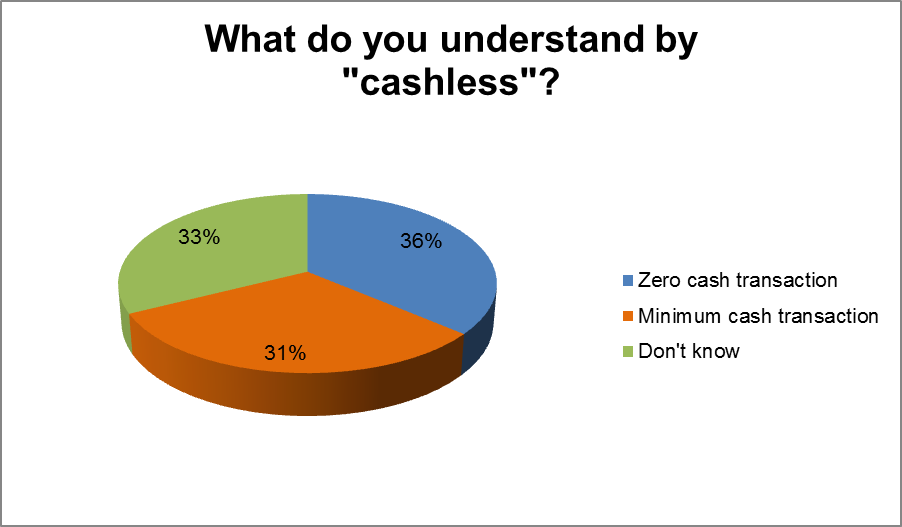

Only one in three survey respondents understood what is meant by a cashless payment.

While 31 per cent respondents think “cashless” refers to a transaction that utilises as less cash as possible, 36 per cent do not know what it refers to. Pushing cashless to such a population is bound to be an uphill task and requires substantial communication on the possibility and safety of cashless transactions. We’re talking about a significant change in imagining economies that are built on non-cash mechanisms.

Second, facilitating “cashless”: How are bank accounts and debit cards used?

A bank account can be key to driving many online, cashless transactions these days – be it through mobile wallets, money transfers and bill payments via cheque, at an ATM or through online banking or a mobile banking app, or direct payment at a vendor through a Point-of-Sale (POS) machine, or for e-commerce. However, what is the predominant form of banking for the average Indian in rural areas?

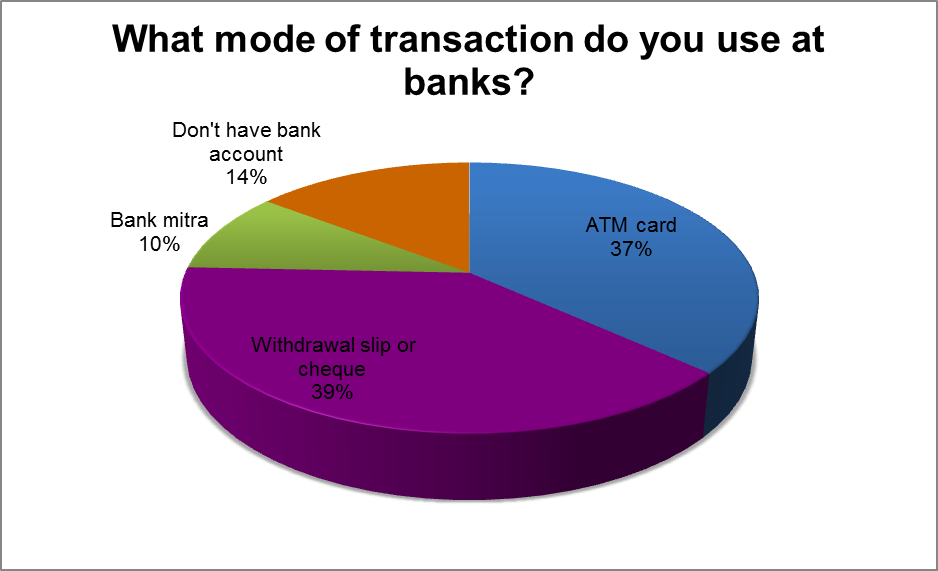

Most sorts of digital payments, including the BHIM app, require some kind of a bank account to transact with. However, much of rural India’s bank accounts only serve as a way to store cash, with banking transactions predominantly limited to cash withdrawal through cheques, withdrawal slips or debit cards at ATMs, as the above graphic shows. As of October 2016, Reserve Bank of India data reports that there are over 2 lakh ATMs and over 15 lakh Point-of-Sale machines in the country, but between these two options for debit card usage, 85 per cent of all transactions done using debit cards was at ATMs to withdraw money[3]. As such, the idea of the most basic form of cashless transactions – through POS machines – still has a long way to go.

It remains to be seen how payments banks, which have just begun to be instituted by a variety of players ranging from telecommunications companies to financial organisations, will change the face of banking and cashless payments in India. The survey shows that 14 per cent of respondents do not have a bank account, despite the massive push through the Jan Dhan Yojana encouraging people to open bank accounts and begin saving and transacting using these accounts. Will a combination of demonetisation, the entry of payments banks and Jan Dhan Yojana lead to an increase in bank account opening and usage in the coming months?

Third, what forms of cashless banking are people familiar with?

Digital India has been a big boost in terms of increasing visibility for moving many kinds of services and transactions online. Has the Digital India campaign – and its adoption by a variety of players including banks, e-commerce players, mobile wallet companies, etc. – helped in increasing the visibility of net banking/mobile banking in rural parts of the country?

Not quite.

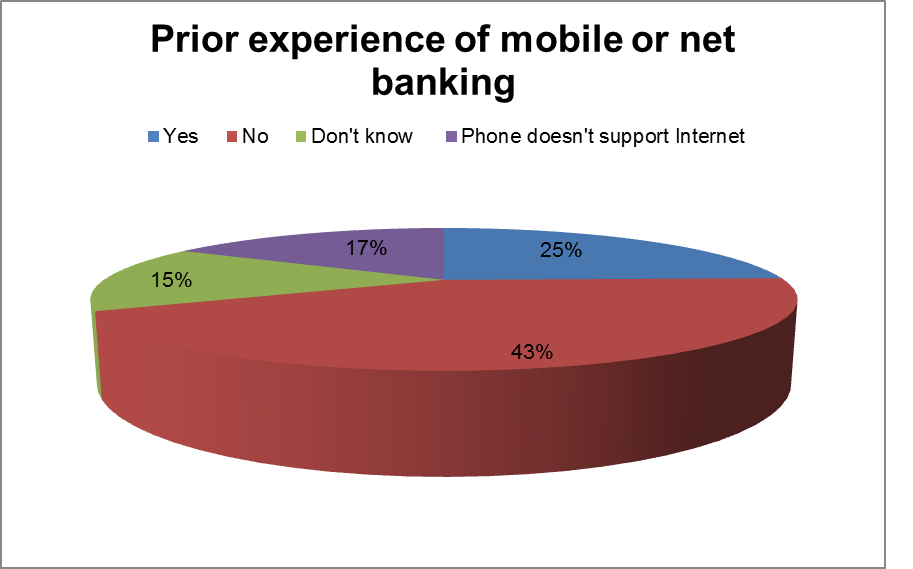

The Mobile Vaani survey post demonetisation shows that only one in four survey respondents have engaged in net banking or mobile banking. Some 58 per cent of respondents have never engaged in these forms of banking before or even know what these mean. Another 17 per cent don’t have phones that support internet, which puts mobile banking or net banking out of reach since most access to the internet in these states happens via mobile phones[4].

And yet, demonetisation has tremendous support

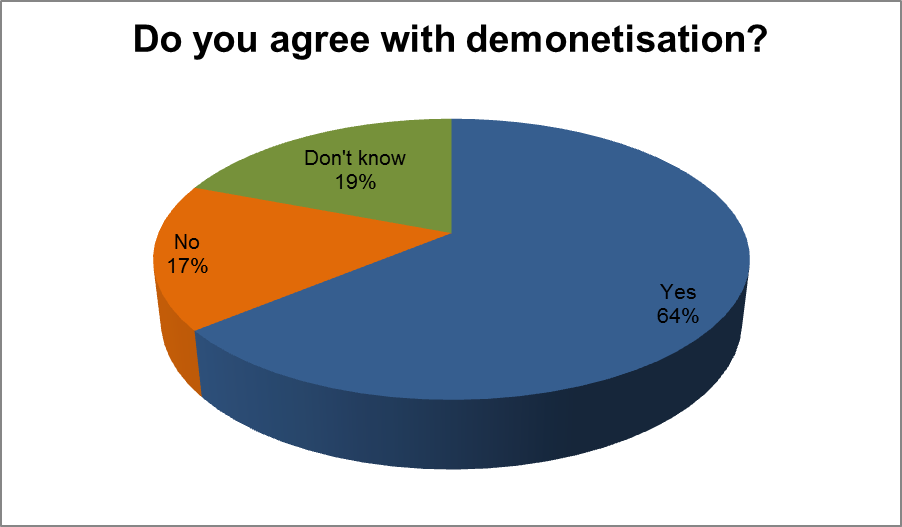

A resounding yes to demonetisation comes from 64 per cent of those surveyed, while 1 in 5 aren’t sure and only 17 per cent say they don’t agree with the move.

Why? It will bring black money out, people say.

An Indiaspend article[5] discusses how the narrative around the objectives of demonetisation shifted from “black money” (used four times more than “fake/counterfeit currency”) during the PM’s first speech on the move on November 8th, to “digital/cashless” thrice as many times as “black money” by the time he made his speech on November 27th.

However, “black money will come out in the open” is the story that has stuck to the hearts of people, going by an analysis of opinions left by people on the Mobile Vaani platform. Even after the PM’s November 27th speech, by which point the black money narrative was not in the picture, nearly 40 percent of opinions to do with notebandi mentioned that the move will bring out black money from the hands of people it’s concentrated in. Of all the opinions that were collected on the Mobile Vaani platform from November 8th 2016 – January 31st 2017, 64 per cent believed that demonetisation will bring black money out. No one mentioned that it was going to lead to a cashless society, much less understand the benefits of such a set-up.

It’s not yet time to go cashless

Necessity may be the biggest reason for people to convert into using new modes of banking and payment, but it does not look like the country is set to go cashless just yet. A combination of poor literacy levels[6] – at 63 per cent in Bihar, 69 per cent in Jharkhand and 71 per cent in Madhya Pradesh – coupled with lack of awareness about safe, digital means of payments, is putting these states on the back burner when it comes to pushing the cashless agenda. It remains to be seen how the sudden push towards cashless payments will be affected as currency circulation inches towards pre-demonetisation era.

Read here for Mobile Vaani’s suggested method to transition hyperlocal economies into working on cashless payments: The right way to go cashless — ICT enhanced value-chains in rural India.

Listen to some interesting opinions on demonetisation:

A song on notebandi!

Farmers struggling due to demonetisation

Demonetisation will put an end to black money hoarding.

Stay cautious: likelihood of crime when using ATMs

Negligence from bank officials when exchanging money

Featured image is from Mobile Vaani’s photo bank.

[1] The survey was conducted between January 4th and 31st and had 370 respondents. It did not collect the name, age, gender or location of respondents.